No matter what has been happening for you this past year, or how you have been attempting to cope, you’re fine. In the same way that all the rest of us are fine, which is to say: none of us are fine. And at the same time, we really are fine.

It’s confusing. Let’s unpack.

In Part One of this commemorative focus on this past year of tender human response and survival to and amidst the global panini, I discussed Dan Siegel’s suggestion that in order to thrive as humans, we need to feel safe, secure, seen, and soothed. Another way of thinking about this, and to once again borrow from the brilliant Dan Siegel, is the window of tolerance.

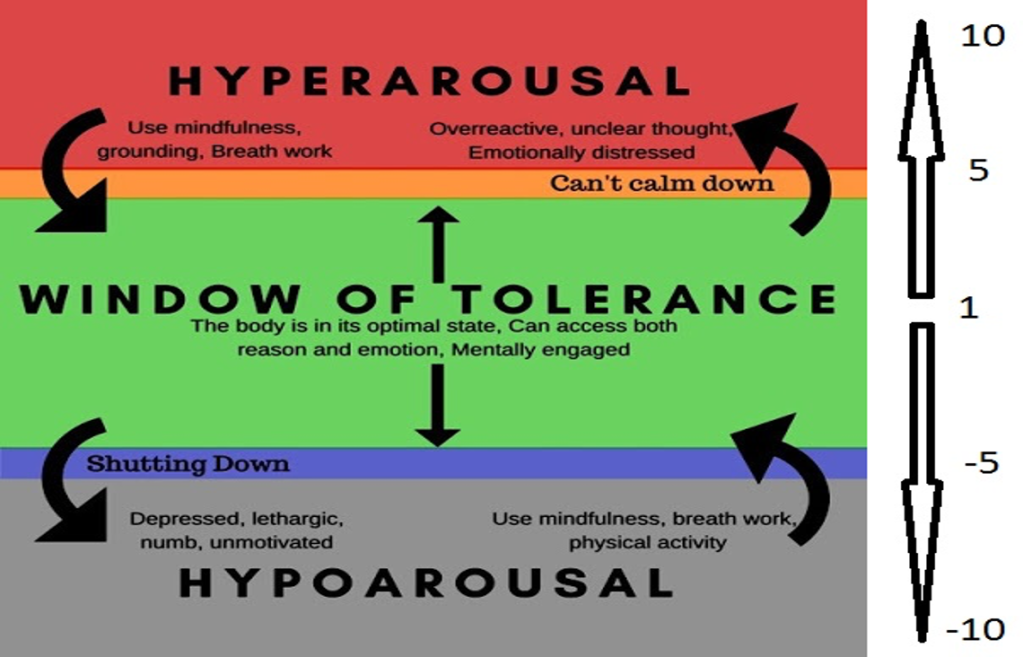

Conceptualizing the window of tolerance works best with a visual, in my humble opinion:

When our needs our met, when we feel relatively safe, secure, seen, and regulated (soothed), we exist in the green space, our optimal sphere: this is the window of tolerance. When in our window, we feel good; we can take what life hands us with a shrug and a grain of salt – people who cut us off in traffic might get the finger but don’t send us into a rage, a friend cancelling plans last minute is disappointing but not devastating. We can respond to life rather than react; we can stay present in our bodies and in the moment: we don’t need an escape route via scrolling our phone or grazing on Cheetos (absolutely NO disrespect to Cheetos though).

Our window of tolerance – how wide it can go – is largely co-created in early childhood with our primary caregivers, through the process of co-regulation. As we discussed in Part One, our early primary caregivers give us huge gifts, sometimes family curses, and often a mixture, through their responses to our emotions and struggles as tiny infants and toddlers. Our internal state mirrors their internal state, and takes its cue from their capacity to tolerate powerful emotions. If we feel safe, secure, soothed and seen when experiencing intense negative emotions, we learn that it’s ok to have such profound and painful reactions, and our capacity to sit with the feeling, knowing that it will be resolved, increases. It’s important to highlight here that we learn to surrender to our intense emotional states when we learn that the feeling will end, that we will transition from the intensity of the moment to a different emotional experience eventually. We cannot do this on our own, particularly as little kids – it’s far too overwhelming for our little bodies to do this on their own. We need a caring adult there to witness and respond to our tantrum, to have their own inner resources of patience and calm and compassion to access, so that we can find a safe place in them to land.

We replicate this over and over and over in our other relationships in life. Witness our kids comforting their younger sibling, or a friend in their classroom. Recall your most special friendships, the people whom you feel safest falling apart in front of, the people who know when to insert a gentle joke, when to listen, when to relate. Think about the co-worker who you scan the room to find and lock eyes with during a meeting in which your boss says something crazy. These are the safe people, the people who bring you home to yourself, to help you access the space inside of you where you remember: I’m OK, this is OK, I will get through this moment, I will be OK, and it’s OK to feel like this at this moment. It’s OK that I’m not OK.

This is living in your window of tolerance.

I could write pages and pages on the window of tolerance; what helps it grow, and what makes it shrink. For the purposes of this post, I want to focus on why so many of us are slipping in and out of windows of tolerance more easily, and what we can do about it. Therefore, I will simply say: those of us who have experienced trauma, be it abuse or attachment trauma, or any of the other myriad ways in which we can hurt and be hurt, will often have a smaller window of tolerance than folks who had a relatively stable and secure childhood with emotionally intelligent and available caregivers. We will more easily slip into hyperarousal or hypoarousal, because our capacity to tolerate distressing experiences isn’t as developed as people who more or less got what they needed as children.

Good news: we can increase our window of tolerance through corrective emotional experiences, through recovery, through therapy, through relationships with people who celebrate and see us. Good news: even if we have relatively little ability to tolerate distressing emotions due to some significant emotional scarring and wounding that we carry, we can always heal – and our healing will be more powerful and transcendent as a result of the deficits that we overcome. The most powerful healers begin from their own wounds.

So, back to COVID and the window of tolerance and why we are struggling so much, and why headlines like Sharp, ‘Off The Charts’ Rise In Alcoholic Liver Disease Among Young Women are bleak and scary and also not surprising: because we need each other to survive, especially in crisis. And when we don’t have each other to rely on, to land safely with, and our own internal resources are totally tapped, due to say, I dunno, a global panorama and the resulting chaos and fear and the need to quarantine in isolation, away from our loved ones and loved things and loved routines, we are going to try to figure out how to stay afloat, how to literally not drown in sorrow and despair.

The truth is, we move in and out of our window of tolerance all day every day, and are constantly trying to get back into our window when we slip (or are pushed) into hyper or hypoarousal – this is a natural process, and one that we do sometimes consciously, sometimes subconsciously, sometimes unconsciously. The need to do this was discussed more thoroughly in Part One.

Let’s say we stay up too late watching a new serial killer documentary on Netflix, or our kid wakes up 2300 times in the middle of the night. We might wake up sluggish, overtired, and dreading the day. We reach for a cup or two of coffee, and the caffeine helps kick us out of hypoarousal and into our preferred state of the operation, our tolerance window. Let’s say that we drop off the kids to school successfully and have a meeting at 9:30, and have ample time to get ready for it. We are relaxed, not rushed, remaining in our window of tolerance. We decide to take a long shower to help wake us up some more, and we are enjoying the warm water cascading over us, relishing this moment of solitude and being in our bodies. Maybe Britney Spears is on the radio, I dunno! Maybe your life is perfect. When we step out of the shower at 9:15, we realize that we missed several texts from co-workers and a call from our boss wondering if we are going to join the meeting that started, actually, at 9:00. Suddenly, we are pushed into a hyperaroused state, accompanied by the age old declaration of “SHITTT!!!!” Our heart races, we are frazzled, we aren’t sure what to do first, and we drop several things as we race to get our clothes on and jump onto our call. Maybe we join the call and try our best to be present and smooth things over, but we remain slightly irritable for the rest of the day – we know our boss will be annoyed, and that weighs on us. We know that the rest of the day is busy: meetings, and preparing for dinner, and picking up the kids, and feeding them, and putting them to bed. The stress is ever-present, a hummingbird in our ear. In this slightly hyperaroused state, we go for a walk, or we focus on deep breathing, and that helps. Or, we reach for a glass of wine, and the immediacy of relief, of routine, of grabbing the wine glass and opening the wine bottle washes over us, promising to douse the internal fire. We exhale.

We are all going to slip out of windows of tolerance all day. That’s normal. We are all going to figure out ingenious ways to get back into our windows of tolerance all day. This is also normal. What is not normal is what we all have been asked to do this past year: to bear witness to unimaginable pain and suffering and loss and rage and fear. To watch entire groups of people, either in a shared reality or a shared delusion, show us what it feels like to go without being safe, secure, or seen. My friend recently took a training with Bruce Perry and he remarked that we all have been disassociating, all the time, throughout this pandemic. I think about myself during the work day, on a Zoom call and sort of present while also looking at things on Amazon while also texting with a friend while also opening up Instagram. Yes, we are all dissociating – existing more regularly in our preferred arousal state, with a lot of energy (working around the clock) or with less energy (lying on the couch and watching TV) than in our window of tolerance. And that is because to be in our window of tolerance means that we are present. Present to life as it unfolds in this pandemic, and what it brings up in us: the despair, the reservoir grief, the anger, the betrayal, the loneliness. These are not feelings that we are meant to process in isolation, without our beloved community. To attempt to sit with all that we have lost and witnessed this past year by ourselves would overwhelm us. So we avoid being present in order to survive this moment in time.

We are going to grieve this properly, when it’s safe to. When we are with our people again, the people who give us a soft place to land. Our friends, our work wives, our crushes, our favorite cashier at the grocery store. Our hair stylist, our regular server, our neighbor with the yappy dog. When, collectively, we feel that the world is less threatening, we will breathe again, and our collective grief will be shared and seen. It will feel overwhelming and amazing and powerful and strange and maybe hard and maybe all of that at once. But the point is, we won’t be alone. We will be receiving, and giving, what we needed when we were younger: presence for one another, gratitude for our shared experience, appreciation for the agony and ecstasy and mundanity of existence, and the reminder that we will get through this, and grow from this, together. That we don’t have to figure it out alone.

That will happen soon – maybe this summer en masse. But for the past year, we haven’t had the connection and community that we needed to tolerate what was happening around us, what was happening inside of us. So yes, maybe you gained weight because you reached for sugar or carbs to either help you get into your window of tolerance, or to get you out of it, out of the present, overwhelming moment. Maybe you started drinking more because your anxiety made your entire body vibrate, and the alcohol allowed a temporary feeling of release. Maybe you stopped texting your friends and crawled into bed for a few days because you needed less stimulation, to be in limbo in a more hypoaroused state. You did the best that you could, to survive this year. Congratulations. You just about made it.

We can’t beat ourselves up for not figuring out how to bypass our humanness and humanity in this past year, for relying on crutches and candy to get us through the day. As humans, we are wired for connection, and we can’t survive without it. If anything, maybe this year will serve to remind us of that. Of what we owe each other, and what we owe ourselves.

Of course, this is a blog that revolves largely around issues of addiction and depression. Sometimes what we use to help us survive no longer works for us – sometimes it becomes something we can no longer do in safety, or securely. Sometimes it stops soothing. If you are worried about your drinking or substance use, or if you are overwhelmed with depression and anxiety, you don’t have to be alone in that, and in fact, you aren’t alone in that. Please reach out, to me or to others who you know have been through something similar. We were never meant do to this alone; we’ve all been courageous and brave for showing up to this year, but we can put down the cross and crutch if it is no longer serving us.